Two summers ago I reported about Typography For Lawyers, the terrific website by Matthew Butterick, a type designer turned civil litigation attorney in Los Angeles. After witnessing one too many typographic atrocities by fellow lawyers Matthew had the brilliant idea to use the typographic knowledge he had gained as a type designer, and combine it with his previous experience at his website design and engineering company to produce a concise primer on typography. Last November Jones McClure Publishing published the companion book.

Based on the popular website, Typography for Lawyers is the first guide to the essentials of typography aimed specifically at lawyers. Author Matthew Butterick, a Harvard-trained typographer and practicing attorney, dispels the myth that legal documents are incompatible with excellent typography. Butterick explains how to get professional results with the tools you already have quickly and easily. Topics include special keyboard characters, line length, point size, font choice, headings, and hyphenation. The book also includes tutorials on specific types of documents like résumés, research memos, and motions.

Why a book about typography specifically for lawyers? As the author explains in the introduction, in 2009 almost one million people were employed in law-related jobs, exceeding people in the print-publishing industry by almost 200,000! Not only is writing central to their work, but what they write and how their texts are processed by other lawyers and judges often affects peoples' lives drastically. Presentation matters, and making texts look tidy, inviting, and easy to read and understand is far more important in law than in most other industries. The possibilities of word processors and the resolution of desktop printers allow those users to produce quality publishing and printing, making professional-looking typography an achievable goal.

Hyphens and dashes: Use them, don't confuse them.

Matthew Butterick perfectly grasps how this type of reference book should look and feel. He doesn't mock around – the opening spread spread already has everything for a quick start. On the left page a Type-Composition Reference charts the most important uncommon characters and how to access them in Windows, MacOS and HTML, while the Summary of Key Rules on the right-hand page provides a handy overview of the 28 most important things one should know about inputting and formatting text. After the obligatory Foreword and a concise and enlightening Introduction, Butterick takes the time to explain the uninitiated reader Why typography matters. And this is where it struck me for the first time why this book is so damn good, a feeling that was confirmed and consolidated throughout the reading of the subsequent chapters. Butterick's strength is not necessarily the fact that he used to be a type designer. It is quite the opposite – the book is such an excellent read because he is a type designer who became a lawyer. He knows very well how to construct an argument, making such a compelling case that he convinces the reader effortlessly. His does so in a clear and personable, almost conversational writing style. And even when he offers the reader the option to be pragmatic and ignore specific rules, you can't help but realise he is right and you are wrong if you do so.

The relativity of point size explained.

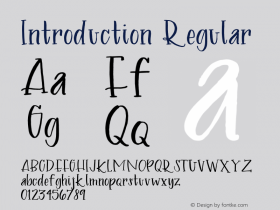

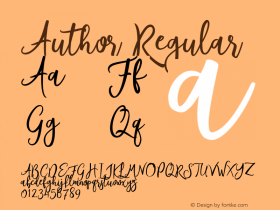

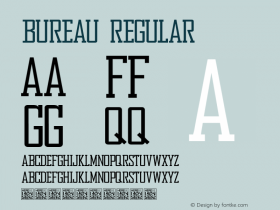

The main content of the book focuses on how to get professional results with the tools already available to anyone working with a word processor, quickly and easily. It is cleverly structured. First the content is broken down in three main chapters, from micro to macro typography: Type composition, Text formatting, and Page Layout. Then each of these three main chapters is split up in two parts, Basic rules and Advanced rules. This allows readers to use the book in the way that is most relevant to them. The information can either be processed thematically, or more experienced type users can skip the tips for novices and concentrate on the latter part of each main chapter. Right in the middle of the book are a brief history of the unavoidable Times New Roman, and Font samples showing common fonts and interesting alternatives for them. The tail end of the book comprises Sample documents and an Appendix.

My main question regarding any reference work on typography always is how it compares to Robert Bringhurst's The Elements of Typographic Style, the mother of all typographic books. As it turns out The Elements of Typographic Style and Typography for Lawyers are perfectly complementary. Whereas the former is aimed at a design audience, the latter has a clear emphasis on the office and business side of typography. The best thing about Typography for Lawyers is that – just like the website – it manages to reach beyond its intended audience. It is not just for lawyers, but for anyone who cares about how text looks, both in print and on the screen. Yes, there are a few topics that are specifically law-related, but they don't interrupt the flow of reading for non-lawyers. Most of all the vast majority of the content is an informative and valuable how-to guide for business typography and communication.

An example of a research memo, before and after improvements.

Of course I'd be remiss if I didn't end this post by taking a look at the design and typography of the book itself. The page lay-out clearly communicates that this is a manual-type of book, with a text area of generous width for the main text, and sidebars holding topic headlines and notes. The text is interspersed with a wealth of examples, illustrations, and before/after comparisons. The different categories of information are easily discernable by their typography, resulting in a very eclectic typographic palette. To be honest I find it a little too eclectic; I would have preferred the use of at least one super family to minimize the number of different type families used.

The main text face is Lyon Text set fairly large. This design by Kai Bernau is a contemporary re-imagining of the types of the 16th-century French typographer Robert Granjon. Sidebars and list indexes are set in two sans serifs originally created for New York museums: respectively the Art Deco geometric sans Verlag for the Guggenheim, and the humanist sans Whitney for the museum of the same name. Technical tips were set in Fred Smeijer's FF Quadraat Sans, which was also used on the cover. Topic headlines were set in Cheltenham FB, designed by David Berlow; captions for typographic examples in Amira by Cyrus Highsmith; and monospaced text in Alix by the author himself; all three released by the Font Bureau. Chapter headings were set in the display version of Robert Slimbach's Arno Pro, which was also used on the splash page of the website.